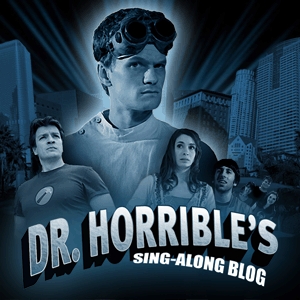

Michael has been a fan of Dr. Horrible’s Singalong Blog for many, many years and I have to say that I’ve never been inspired to even be a little bit curious about it. Simply put, it doesn’t sound like something that I would enjoy. A little goofy, a little super villainous, and I had to be suspicious because I knew exactly one thing about it— that it starred Neil Patrick Harris. Consequently, in Michael’s eyes, it could be an absolutely miserable piece of artistic dreck, and he would still love it.

So, given that it came out during the writer’s strike in 2008, I’m a little late to the party. But our whole family watched it last night and first of all, I should say right up front that it was fun and entertaining and what else do you want from sitting in front of the tv for an hour?

But also, it gave me about a hundred different thoughts about what a movie is, or could be, and what it appears to be when you are an audience member.

In the recent issue of The Atlantic, there was an article about Tom Hanks, which I really enjoyed. It was a bit of a puff piece, but I genuinely did enjoy getting to know a bit more about him, having grown up right around his heyday in Splash and Big and Sleepless in Seattle. He is just now publishing his first novel, which is about moviemaking. He explains why he wanted to write it this way: “I have found that absolutely everybody assumes they know how movies are made, and nobody does.” And then: “Making a movies is exactly like starting a business, waging a war, getting to the moon, figuring out how to treat a disease, or coming up with public policing in order to make a city work better… Making a movie is as unknowable and as complex as any great saga or odyssey that is wrought with many turns of fate.”

I have to say that when I read this, I immediately believed him. I understood him to be saying that it’s just so complicated to put together a movie, to hire on a couple of thousand people and schedule things, and have unexpected things come up— it’s all some huge managerial and collaborative task that also has to stay true to some artistic vision through its problem solving. And because of that, every movie is its own thing. Each time someone goes to make a movie, it presents challenges that can’t be adequately anticipated beforehand, and it becomes its own sort of world.

But as an audience member, this is really counterintuitive. Because if there’s another thing that movies almost always are, it’s formulaic. For instance, I just watched a movie on the plane called “About Fate,” and it was cute and light and fun, but not only did it adhere to a script, I mean, it really adhered to a script. By the end of the first scene/montage, I practically could have hit pause and then told you the entire rest of the story.

The story centers around two people who are both in sort-of bad relationships, and they meet by chance, dump their other people and wind up together. Which is a fine story, of course, and the gimmick in this case is how parallel their stories are, which is also fine. But the way the plot-points are portrayed is also incredibly circumscribed. One of the important subplots of the story is how the female heroine feels like a failure in her sister’s eyes and her sister is always screaming at her, and the two of them don’t get along. And right before the climax of the movie, there’s a scene in which the sister comes to her, lovingly, and just says shyly, “why do you hate me?” And the viewer is like, “What? That’s such an inversion!” It feels as much of a confrontation to the viewer as the sister, because that hasn’t been what their relationship has been like at all. And the writers use that moment to have the heroine realize that she can go after what she wants after all, and the story launches itself forward.

As a viewer, we just accept it. This is what a movie calls for. Our heros were stumbling around, stuck in their own foibles, and then something happens and they are stirred to action, and then we can get on with wrapping up the story which we know must resolve. Those are the rules of movies, and we won’t feel whole without it.

So it’s easy to gloss over the fact that this particular event makes no sense. We haven’t been given any reason to believe that she hates her sister. In fact, we’ve had a well-developed sense of their conflict that doesn’t include this little reveal. We know that the sister is self-centered and unkind, and there’s nothing that leads us to believe that she would gently come and tell her sister to go for what she wants and encourage her.

Nonetheless, we accept it really with no problem, because it’s the thing that lets the story do for us what we want it to do; descend into the world of our protagonists, understand their misery, and then get on out of it to a happy ending. And by these standards, About Fate is okay. It does the best it can with what it has, and it’s fun and pleasing.

But then there’s Dr. Horrible’s Singalong Blog, which doesn’t do that, but instead does something radically different. I should say that it’s perhaps unfair to be talking about this in the scheme of movies, because it isn’t one. Technically, it’s three 14-minute episodes that only after-the-fact were put together on a DVD. But it still has a story, and the fact that it is different is every bit the point. It doesn’t adhere to the formula or the rules, and yet it comes out with joy and verve and success. Why?

I’m going to go a little bit afield here, but I think an analogy will help me articulate a really satisfying answer. I (somewhat) recently read a book called Don’t Trust Your Gut: Using Data to Get What You Really Want in Life by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz. In one of the chapters, the author spends some time looking at who succeeds on dating websites. There are some lovely and surprising insights (if you can stomach economic ideas about what sort of racial-gender combinations come at a “discount” because of prejudice, I recommend the chapter because it’s fun and interesting.)

In the book, he cites the work of mathematician and author Christian Rudder. Here’s what he writes.

The mathematician and author Christian Rudder studied tens of millions of preferences on OkCupid to learn the qualities of the site’s most successful daters. He found— and this was not at all surprising— that the most prized daters are those blessed with conventional beauty; the Brad Pitts and Natalie Portmans of the world.

But he found, in the mounds of data, other daters who did surprisingly well: those with extreme looks. Think, of example, of people with blue hair, body art, wild glasses, or shaved heads.

Why? The key to these unconventional dates’ success is that, while many people aren’t especially attracted to them, or find them plainly unattractive, some people are really attracted to them. And in dating, that is what is most important. (Page 2).

And so, here’s what I have to say that extrapolates this insight into the world of movie making. If you’re going to create a romantic comedy, the single best thing you can probably do is create When Harry Met Sally, or You’ve Got Mail or Jerry Maguire. Star power, a great premise, whip-smart writing, and characters that roll forward so beautifully so that even though you know what’s going to happen, you are riveted in watching how it all unrolls. That would be the dating website equivalent of your George Clooney, your Robert Redford, Audrey Hepburn, Ingrid Bergman, Scarlett Johansson, whomever else. Those beauties knock the rest of us out of the water the way that those movies blow past About Fate in the first scene.

But if you’re not going to do that, maybe relax and be unapologetically, extremely weird. If you do that, there are plenty of people who are going to walk away after the first scene and say to themself, “Not my cup of tea.” But for the people who stay, it’s going to be an awesome romp of delight.

And that’s what Dr. Horrible’s Singalong Blog does, it makes its own rules. Right away, they freeze-frame the action in fantasy, letting you know that they’re doing their own version of realism and hero movies. In some places in the movie, the protagonist didn’t interact with the people right in front of him, almost the way that a stage actor can narrate right over the goings-on directly next to him, directly addressing the audience. They break out into song in the middle of sequences, and a weird chorus appears intermittently. This is a world in which wonderflonium exists right outside the typical laundromat.

In other places, the writers and actors leaned so heavily into cliches that it came right out the other side and felt fresh and beautiful. For instance, the protagonist refers to the other characters as “my nemesis” and “the girl of my dreams,” but this works. Evil Horse turns out to be an actual horse.

This is the dating website of purple hair and an usual number of piercings and what can I say? It’s some people’s cup of tea. A lot of people’s, actually— it has received a lot of critical acclaim. And I’d posit that it really isn’t that marginal. There is some fine storytelling, and I think that people are actually eager to suspend their disbelief, and enjoy the 42 minutes of a world where we root for a guy to defeat his nemesis and get the girl of his dreams.

And maybe Tom Hanks’ insight is not only the way to inspire a novel, but it’s own sort of advice to movie-makers. If each movie really is its own thing, a world unto itself, maybe it would be a more enjoyable world where the storytelling of the script weren’t the tightest thing about it. Maybe people want to suspend their disbelief a little bit more, enter worlds that are slightly weirder than just a weird premise or gimmick. If you let artists fly a little freer, (dye their hair, or tattoo their bodies, metaphorically speaking), maybe we’d come out with more movies that are little bit more like Dr. Horrible’s Singalong Blog and a little less like About Fate. And that would most assuredly be a good thing.