Last week, our indoor cat found a small opening to the wide world, and disappeared for around 100 hours before he eventually launched himself back in through a cracked window. When he came back, I had to really look at him, so did everyone, it turned out— because we all considered that maybe somehow this wasn’t really him. His sister, the one who curled up with him, day after day, now hisses at him. It’s hard to say exactly what has changed; he begs for attention a little differently, and he sleeps in a different position. And as for what has changed for him, we’ll never know really, of course. He’s a cat.

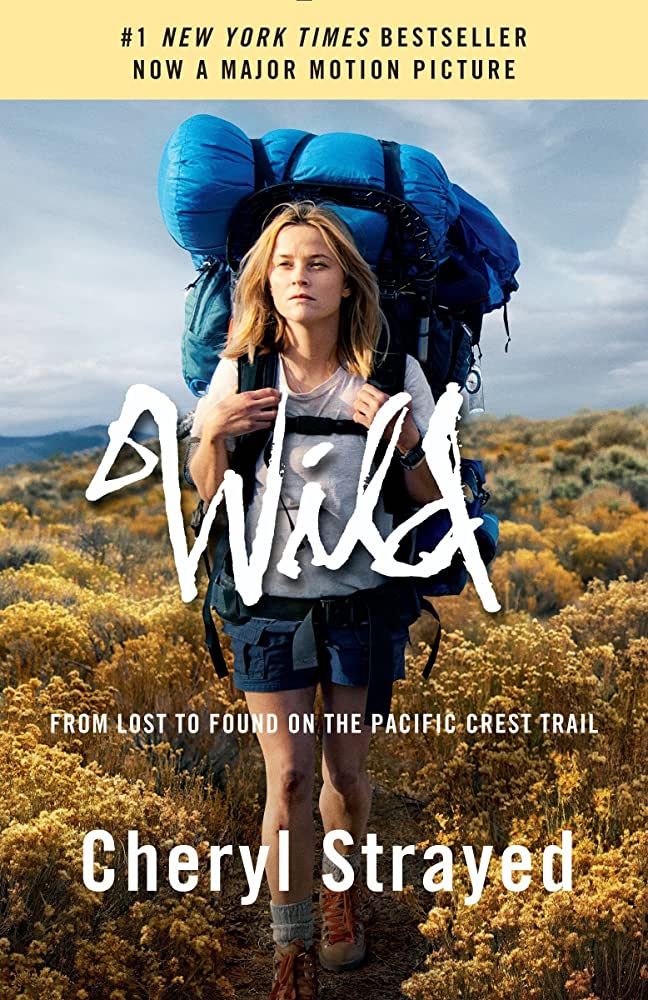

But it’s hard not to project on him the human experience of a transformative experience, the kind where you see or do something and then have the opportunity to put everything back in a different place. Perhaps I’m just thinking of this having reread Wild by Cheryl Strayed. It’s the story of a woman who hikes the Pacific Crest Trail, and in the process reconsiders her ended-marriage, her infidelity, her mother’s death, her childhood, her relationship to money, her addictions, and ultimately what it means for her to be a woman in this world.

When I first read it several years ago, I was totally captivated by it, and when I got to the end, I marveled at this: when you hike a trail for a couple of months, it is nothing if not monotonous. Day by day, the same type of rocks guide you, and the trail looks the same. Eventually, each campground looks like the last, and who can tell apart one stream from the next? Forget watching water boil. At the speed of walking, the landscape changes like an glacier moving steadily forward, an inch at a time. Narrating a long hike is like writing that scintillating story. Not only that, but the book was published over 15 years after her hike. How did she remember the details of the rain, the meals, the tarps, the terrain— enough to give them life over a decade later?

And yet, the book moves forward with so much pluck and momentum. We are rooting for this journey in so many ways, rejoicing in the small pleasures of the trail and grateful for our own un-blistered feet. I felt so incredibly engaged through the entirety of the book, so it wasn’t until I closed it again this time that I realized that I could barely say what had happened. There is no grandiose drama, there is no climactic ascent, and there isn’t even any sudden realization or healing. She doesn’t dramatically proclaim that now she has done this, she feels better. We just get to watch a person unfold herself in front of us, and her brave facing of her physical limitations gives us the confidence that she is growing.

I have a lot of heart from the extremity of what she did, starting with ambition, but deciding to tolerate the discomforts— the unanticipated, extreme discomforts— that came not so much out of single-minded ambition, but out of the way she had set up things so that this decision became almost like the trail itself: nothing left to do but pack up and set out again, keep moving forward because what else are you going to do?

And the kinds of realizations she has along the way, she has the opportunity not to heal the grand pain she set out with— the loss of her mother— but the hard-earned chance to see the world a little differently. At one point, she spent her last dollar, and is left with two pennies. As she considers tossing them to make a wish, she says, “I probably wouldn’t have been fearless enough to go on such a trip with so little money if I hadn’t grown up without it. I’d always though of my family’s economic standing in terms of what I didn’t get: camp and lessons and travel and college tuition and the inexplicable ease that comes when you’ve got access to a credit card that someone else is paying off. But now I could see the line between this and that— between a childhood in which I saw my mother and stepfather forging ahead over and over again with two pennies in their pocked and my own general sense that I could do it too” (280).

And if you really pressed on this change, if you could interview her, and ask: Cheryl, what changed for you in your relationship to money after your trip? I can imagine her saying, Nothing really changed. I still didn’t have any money, I was still scrappy and made do, and fearless, and I still resented a childhood that didn’t give me many opportunities.

Which is maybe why the book is so satisfying. It doesn’t promise anything more than it can give. It feels honest and true, and yet offers a glimpse of what it means to take your story and look at it differently. And then the artistry to make it all feel that way, literally out of a pile of rocks, makes me think that Strayed is one of the most extraordinary and under-sung American writers. If she thought she was teaching me about altitude and streams and trail markers, she was instead teaching me about the benefit of time and insight, as well as the gift you offer the world when you use words and sentences and grammar and craft to explain it all to the world.

And there is, of course, the lesson that she wants to impart, the one she tells us in the prologue:

“I looked north, in its direction— the very though of that bridge a beacon to me. I looked south, to where I’d been, to the wild land that had schooled and scorched me, and considered my options. There was only one, I knew. There was always only one.

To keep walking.”

We need more stories like hers.