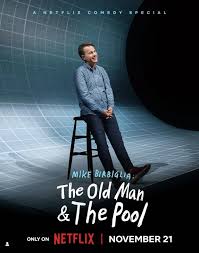

For the past three nights, I have ended my day by watching a Netflix special by Mike Birbiglia called The Old Man and the Pool. It was recommended to me as an example of the way that a writer can weave together stories and call-backs, but I found that it was much more than that. It was extraordinary.

I don’t watch a lot of stand-up comedy— I think the only time I paid to see a comic was when I went to see Jerry Seinfeld perform in Tel Aviv, and I can’t even tell apart my delight in his jokes from my deep and temporary lifting of my homesickness as he described tv dinners, rude walkers, and other quintessential Americana. Seinfeld is, of course, also a master at holding an audience captive, using wry observation, tight wording, physical drama, and gorgeous storytelling to spellbind a group. (It helps that people show up ready to feel light).

But Birbiglia is no slouch either.

Here’s what I want to say about Birbiglia’s piece: he takes us on a very dark journey. He starts with a body that might be ill, and takes us straight to the heart of the deepest fear, one that gets written in large letters on the sparse and versatile set in the background: I might die soon.

He makes this deal with the audience, right away: I promise that this will be funny. I promise that every time I give you some horrible bit of news, I will take away the pain with laughter.

Throughout the show, he tells of many people in his life who have died. The first person he discusses is his grandfather, who retired from a dangerous career, but still died when he was 56. Here’s Birbiglia’s words:

“And then after that, he worked at a bodega in Bushwick.

And supposedly one day, one of his regular customers came in and said, “How’s it going, Joe?”

He just keeled over the counter and died.

Which is sad.

But it’s also a pretty funny response if you think about it.

[crowd laughs]

In some ways, he was the original comedian of the family. That’s an extraordinary level of commitment.”

Birbiglia is a master of timing, so he lets us have that moment of sadness, a quiet moment, before turning it around for us. Right after he tells us that his grandfather has died, he tells us that it’s okay to laugh at the absurdity and irony of it.

And he builds a lot of trust that way, to tell us that no matter how uncomfortable we are going to feel, how sad we might get, how profound the losses are, he is going to help us come out of it. It’s not going to be for long, and we are going to get to laugh.

That’s pretty powerful stuff, and he puts it to good use. Not only do we deal with the grief of losing loved ones, but the fear of it, the things unsaid, and ultimately, the confrontation that we will all die as well. That threat, the realization, hangs over the entire show, but he doesn’t let himself say it until the very last minute, when time is running out— as it does.

Birbiglia teases this ultimate ending rather than say it outright. The light is a coffin. His nightlight goes out. He brings us to the brink and lets us laugh, and it’s exactly the awe of being adjacent to the Grand Canyon, the even grander abyss.

But since I’ve seen it three times now, there’s another moment that I want to talk about, the moment that in a traditional narrative arc would be the climax. He is about to pull it all together for us, he has threads running everywhere that he’s about to yank on…

And then he tells us that a man died last summer, from holding his breath underwater at the YMCA. That’s funny, right? In the hands of a comic, it’s pure gold. Mysterious, tragic…sure. But also, what a funny way to die. Kind-of like a grandfather who, committed to the craft of humor, keels over and dies on a counter.

But Birbiglia doesn’t let us have the moment. He says that there must be a moment of silence to honor this tragedy. People laugh, because he must not be serious. But he seems to be serious— he scolds. He insists.

The moment drags on. The laughter comes intermittently, and it’s not because anything is funny. Actually, at this moment, nothing is funny. The content in front of us, that a man has died, has never been funny. And now, our comic, our interpreter, has told us that it isn’t funny. He has broken the rules which he set out, in which we were always allowed to laugh.

Now the laughter comes because people are uncomfortable. The guide to humor-through-darkness has asked us to reconsider: is there anything funny about this at all? Birbiglia has good-naturedly enjoyed his own jokes with us all along, smiling along with our laughter, now finds nothing funny. He makes the audience repeat after him a solemn vow to have a moment of silence in honor of this unnamed victim of his own competitive breath-holding. It is all so tense, and uncomfortable. The audience repeats, slowly coming around to learning a new set of rules in which laughter doesn’t dissipate the uncomfortable truths.

And then. Then. Finally. He relents. He gives us our moment, he lets us laugh. We are back to how we were.

Birbiglia pulls the threads together, leaves us with just the right amount of wholeness, and takes his well-deserved bow to thunderous applause. It’s admiration and relief, in equal measure.

He has checked all the boxes for humor, but he has done more. He has let us come inside his worries, his family, his fears, and his love. He has made it easy to take a sideways glance at the end of everything.

The first time I watched it, I laughed at every joke. Each time I rewatched it, it seemed more and more dark, until he seem to have created a lightness out of darkness itself. Each tender story, an echo of the greater gaping void. It took me underwater and back out, and all I can say is that it is good to be alive.