Which is better, to be right, or to be happy?

I suppose that there are families where that isn’t the central question, but it was in mine, and really, it wasn’t so much a question as a conviction: to be right is to be happy. As an adult, when I say this out loud, it sounds ridiculous. And yet, I can’t quite get my sunken teeth out of the flesh of correctness.

And in the midst of articulating the miserable way of being programmed to think that you will win friends by asserting hidden and uncomfortable truths, one day, a friend looked at me and asked, “Have you heard of the Ibsen play, ‘An Enemy of the People’?”

Why no, no I hadn’t.

Google to the rescue and— how had I missed this gem?

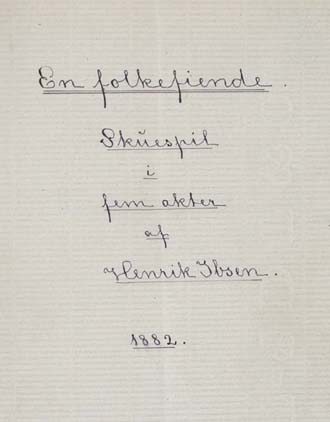

This play was written by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen in 1882. In Norwegian, the title is Folkefiende, (a delightful pseudo-cognate), and it’s been performed in various English translations on Broadway alone ten times, the most recent opening this past month.

The play follows the story of Doctor Thomas Stockmann who discovers that bathhouses in his town, newly opened and celebrated for their healing powers, actually harbor bacteria and disease. A man of conviction, he is left alone to sound the alarm, warning the mayor (his brother) about the health threat, even at the risk of disrupting the town’s anticipated summer commerce. While at first it looks like the good doctor will find a sympathetic hearing among the powers-that-be, one by one they turn on him, preferring a self-deluded narrative that goes down easy rather than wrestling with the consequences of seeming alarmist.

The tragedy of the play is that, of course, the doctor is right. He has to choose whether to stand by his convictions or whether to stand down and maintain every friendship and relationship he has, as well as soothe the worries and woes of his entire town.

In art, we tend to love and root for people like the good Thomas Stockmann. Even in the historical rear-view mirror, we tend to like people like this. In real life, we despise them, just as the characters do in this play. And I honestly think that we know this, and that’s what makes it good and compelling art. In the audience, we see how right and righteous Dr. Stockmann is, and we have the illusion that if we had been in his town, we would have stood by him, even as we are being instructed: no, that’s not how the world works.

And it is this tension, between the way we wish we could be, and the way that we humans truly are when it comes to catastrophic threats that was exploited in the recent staging of the play on Broadway, on opening night.

What happened on opening night? Sparks flew, the gauntlet was thrown, the play was disrupted.

Here’s how theater critic Vinson Cunningham explained it in the New Yorker:

At that moment of high drama, one environmental protestor in the audience after another got to their feet and began to fulminate about the climate. “I am very, very sorry to interrupt your night and this amazing performance!” one shouted. “The oceans are acidifying! The oceans are rising and will swallow this city and this entire theatre whole!” The protest action, with its references to science and to government inertia, and with its tightrope walking along the boundaries of free speech, perfectly matched the tone and content of the play.”

The New York Times critic, Jesse Green, explains it thus:

Their timing, just after a pause between acts that included a surprise pop-up activation onstage, was exquisite. As part of Gold’s concept, some members of the audience who were already milling about on the set remained to “attend” the town meeting that followed. Because the house lights were deliberately left on to emphasize that mix of cast and audience — as well as the interpenetration of past and present, fiction and reality — I was certain the protest that immediately ensued was part of the show.

Certainly apt were the protesters’ costumes (statement T-shirts) and catchphrases (“No theater on a dead planet”).

It’s no surprise anyone that Ibsen’s play would be the right location for a protest about climate. The entire conflict of the play is what it means to sound the warning alarm about imminent destruction, and the incredible forces which come into play in order to willfully look away from a threat in order to preserve the status quo, at least a little bit longer.

To sound the warning alarm feels, always, like you will be thanked. To know the truth and to bring other people to the truth feels like a public service. To avert disaster.

Here’s the thing about warning bells though. They are only that in retrospect. Trying to get other people alarmed about something you see is an actually crazy endeavor.

For every Ibsen’s Enemy of the People, there’s a Boy Who Cried Wolf. The abuse of alarmist messages, the fact that we can spot aberrations in data long before we know if it is building towards a trend or a passing aberration, means that we could be worried about things all the time.

At least I could. My city wants me to do earthquake preparations. Also maybe flood preparations, and why doesn’t may family have a few days’ stockpile of food and water? The CDC is saying both reassuring and alarming things about the latest spotting of Bird Flu— is this the next pandemic that is probably going to happen in my lifetime? The rise of monoculture means that our food supply is more in jeopardy than most people realize. That rice shortage a few years ago was a warning shot across the bow if there ever was one. Democracy is failing. And of course, the oceans are rising and the planet is warming.

It’s not unreasonable that Dr. Stockmann’s colleagues chose to put their heads in the sand. The unreasonable thing is that we in the audience entertain the idea that we would have done any differently.

Of course, believing that we would have is precisely the enduring pleasure of An Enemy of the People. Dr. Stockmann’s obvious correctness convinces us, and it helps that we don’t stand to lose anything by believing him. It won’t be our town that plummets into poverty, bankrupted by closed bathhouses, after all.

Still, if you would like to be disabused of that notion, in the interest of being right, you have only to think of those protestors disrupting the show. What happened, after all, to them? The critics don’t say, but we already know, don’t we? They were escorted out of the theater and the play went on, continuing its warning of what will happen if we don’t act in time.