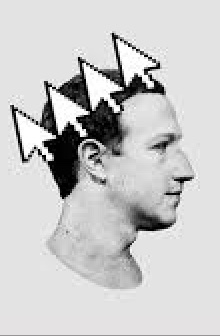

The recent issue of The Atlantic offers an “opening argument” by executive editor Adrienne LaFrance entitled “The Despots of Silicon Valley.” In a move worthy of Mary Shelley, LaFrance creates a villain out of: the 20-year-old text messages of Mark Zuckerberg, a manifesto written by Marc Andreesen, as well as some vague hand-waving towards Elon Musk. In this mashup, individual actors become “these people” and he calls them “hypocritical, greedy, and status-obsessed” (12).

Let’s been generous for a moment. LaFrance is trying to point out that there are a few private technology companies based in Silicon Valley which hold inordinate sway over our country’s politics— and possibly well-being. Enough cannot be written about the effect of social media on the teen mental health crisis, neither is there a large populace of healthy happy adults running about this country while on their phones. But LaFrance doesn’t say much about that. As the ills which stand in for the rest, she cites: a Facebook study in 2012 in which they experimented with manipulating user emotions, its “participation in inciting genocide in Myanmar in 2017” and its “use as a clubhouse for planning and executing the January 6, 2021, insurrection.”

At the top of this demonstration of big tech’s evils, she puts up leaders who “worship at the altar of mega-scale” and believe in their mission. The word “worship” is telling here; elsewhere LaFrance gestures towards almost religious views: “They tend to hold eccentric beliefs” (12) and “This position, if viewed uncynically, makes sense only as a religious conviction” (14) and gestures at “what might be considered the Apostles’ Creed” (14).

(If these impute some religious position to these tech titans, it only suggests to me the extent to which LaFrance herself could be understood here as a preacher, determined to take down the devil.)

Personally, I don’t think it’s necessary to impute any bad motives; why not assume that the technologists are interested in what innovative, adventurous, and inquisitive artists and scientists have always been interested in: how far can we push this thing?

Here’s a story I learned recently about that impulse. When the people of Florence, Italy, outgrew their previous cathedral, work commenced on a new one, in 1296. But the structure was larger than any building ever built before. Meanwhile, Florence had outlawed the use of buttresses— an architectural technique that offered support for a roof, but was considered gauche and ugly. That meant that nobody knew how to put a roof on the building— the technology literally had not been invented. It took over 100 years before Fillipo Brunelleschi was able to solve the technical problems, invent a new way to put up a roof, and complete the building around 1436.

It’s kind of amazing that nobody said, at the very beginning, “hey, maybe we shouldn’t start work on a building with no idea of how it’ll work out to complete it.” But then, perhaps we would not have the Duomo di Firenzi, the enormous Florence Cathedral. Pushing boundaries was the work of architecture in the Renaissance. It’s always the work of innovators and artists to push the boundaries. Nowadays, the open frontier is information technology. (And CRiSPR/Cas9 but that’s not yet at the level of moral hysteria although it arguably should be).

To assume that inventors should only be allowed to play in the playgrounds of what has already been established and deemed safe is exactly the idea that Andreesen is shaking off, but LaFrance misses the romance and takes it to be a kind of political self-aggrandizement.

Here are two telling paragraphs from the article:

“Our enemy,” Andreessen writes, is “the know-it-all credentialed expert worldview, indulging in abstract theories, luxury beliefs, social engineering, disconnected from he real world, delusional, unelected, and unaccountable— playing God with everyone else’s lives, with total insulation from the consequences.”

The irony is that this description very closely fits Andreessen and other Silicon Valley elites. The world that they have brought into being over the past two decades is unquestionably a world of reckless social engineering, without consequence for its architects, who foist their own abstract theories and luxury beliefs on all of us.

The fact that LaFrance finds in Andreessen’s words an inadvertent self-description only shows to me how poorly she misunderstands what Andreessen is talking about. I suspect that Andreessen has in mind when he writes all of that is someone like LaFrance herself. At the end of his article, LaFrance writes, “it has become clear that regulation is needed,” “Much should be done”, “Universities should reclaim,” “Individuals will have to lead the way,” and “That should include challenging existing norms.” That’s a lot of prescription-writing. Might not this be the kind of “know-it-all credentialed expert worldview” that Andreessen is writing about? The kind of pontificating without consequences? A person, unelected and unaccountable, but telling people what they ought to do, in a sort of abstract theory?

If LaFrance is the sort of person that Andreessen has in mind when he writes this, we might think of it a little bit like a child’s temper tantrum; a little kid told that he has to get off the playground just as he has discovered the great fun of sliding down the slide backwards. It’s not that LaFrance (or we all) don’t foresee the great catastrophe that might result from such reckless behavior. But how does it help to misunderstand what Andreessen is saying, misconstruing the fun and adventure that he is after?

In his manifesto (which LaFrance quotes at some length) Andreessen cites his desire for all of the fun of breaking boundaries. Probably just his first sentence will suffice:

“We believe we should place intelligence and energy in a positive feedback loop, and drive them both to infinity…”

What does this mean, really? Intelligence and energy are positive intentions, and the combo gestures at the idea that nobody should be allowed to put the brakes on someone else’s passionate inquiry. We have speed limits on public roads, but we make space for people who love cars to boast that it can go “0 to 60” in however-many seconds, and also for people who would like to boast that their car “maxes out at two-hundred-whatever mph.”

How do they know that? I used to wonder as a child. As far as I knew, there were no roads where you could find that out. And also: why do you care how fast your car can go if you can never drive it that fast?

But here’s the thing: we understand that some people have that love in their hearts, and we don’t put artificial caps on cars that make them start braking at the speed limit. And we don’t really have to. It turns out that people maxing out their car speeds is a negligible contributor to car accidents; we get a lot further by letting people keep all of their liberties of the glee of imagining (experiencing?) their fast car, and focusing our efforts on stopping drunk driving, where we don’t allow people liberty.

The people who have a fire in their belly, a gleam in their eye, a desire in their heart that wants to build the biggest domed roof that has ever been built, or make the world’s largest network, or make the fastest car— these are innovators we can’t live without. Figuring out how to make safe, speed-regulated streets for the rest of us is the trick. But it really doesn’t get us very far to demonize those who dream big, whatever their motivations.

And for the record, I might have been more sympathetic to all of LaFrance’s arguments if she hadn’t really crossed a line in mischaracterizing where I live. She can make teenage-Zuckerberg a jerk (I find this uncompelling— hyperbole is a characteristic of adolescents, not an indicator of sober adult moral decay), and she can make Andreessen out to be a wannabe fascist, but how does that speak to the rest of Silicon Valley?

To assume that these few tech titans speak for all of us, by virtue of living here, or their place of employment? Good lord, LaFrance.

She writes this: “Key figures in Silicon Valley, including Musk, have clearly warmed to illiberal ideas in recent years. In 2020, Donald Trump’s vote share in Silicon Valley was 23 percent— small, but higher than the 20 percent he received in 2016.”

How did this insinuation get past the editors at The Atlantic? Is it because LaFrance is the executive editor, got personally invested, and overruled good common sense? The evidence that “key figures” have “warmed to illiberal ideas” is that Trump’s percentage of the vote went up three points between 2016 and 2020? Can you even think of any worse evidence?

I don’t even know what “Silicon Valley” she’s talking about, or how she got her numbers, but I’ll share what it’s like from my perspective: almost everyone I know supported Biden in 2020 in the general election. The Trump voters I know have nothing to do with the tech sector; one of them is a small business owner, another a neighbor. They both take as a principle of truth that the government is corrupt and think the best thing they can do is take Trump up on his offer to “drain the swamp.”

I know that my anecdotal data is hardly any better than LaFrance’s allegation, suppositions based on not-much. But at least I haven’t made two people’s ideas speak for the many, exemplify a trend, capture something about this place and a kind of runaway power grab. California in general, and Silicon Valley, remains almost unforgivably liberal, and neither Andreessen nor LaFrance speaks for me, nor for the thousands of people from around the world who move to Silicon Valley to improve the action of push-buttons or shipping notifications, or ad targeting, or other small projects from home offices, never so much as catching a glimpse of reclusive tech titans on their private jets.

And if LaFrance wants to suggest a proto-fascism implicit in the dreams of innovators and artists, she ought to cite something more than Trump’s poor showing in a county that (electorally) rejected him summarily.

The leaders of these companies don’t need to be despots (or demons) in order for us all to summon our collective will to make healthier, happier, and more secure online spaces.